Authentic

An art appraiser is 95% certain this Gauguin painting is a fake. But 95 is not 100...

I must say it’s an excellent fake.

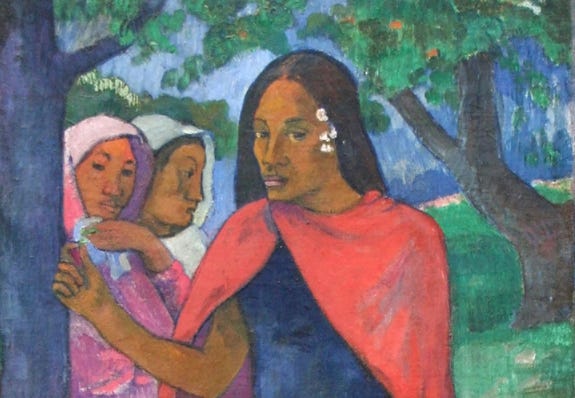

The forger captured not only the colors and textures of Gauguin’s first Tahitian period but, more essentially, the spirit—a view of the world that is wistful, bizarre, yet oddly inviting. A simple composition: a girl and an older woman sitting beside a pond or stream, a white dog lying on the grass. The tableau evokes, without copying, the famous painting in the Musee D’Orsee called Joyousness. It also foreshadows that grand canvas Gauguin himself deemed his masterpiece and titled—pretentiously even for him—Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?

Eternal questions to which he never found answers.

But then, who of us has?

The pallet certainly is convincing: greens, browns, muted orange, white flowers, highlights of pink and dark red. And the two women are exquisitely rendered—soft, rounded forms, brown faces with broad noses, mysterious, playful eyes. Gentle, knowing eyes, so like Tony’s. Perhaps that’s why I keep staring at the painting on my wall, when I should be on to other business.

So, with all of that, why am I so certain it’s a fake? Partly instinct. The forms and composition feel too careful, almost fragile in their arrangement—more like the hand of a skilled copyist than of a master delving into the power of his idealized primitive world. Then there’s the provenance—a little too convenient. A picture matching the description, titled Morning Light, is included in the catalog of the October 1894 exhibit in Paris, but not reported as sold. After that, it disappears from the record. In 1949, this picture was discovered in an attic in Dreux. Of course, many paintings disappeared during World War II—with a comparable number of forgeries surfacing in the following years.

My current hypothesis is that it is the work of Nahrheit, the Swiss expert who successfully forged works by nearly every post-Impressionist of note. Nahrheit considered himself an “artist of the wrong time” and, late in life, famously demanded that critics tell him why his Picasso was any less authentic than one by that unpleasant little man who happened to be named Picasso.

What is authentic after all, he wished to imply. Ridiculous question.

Staring into the old woman’s eyes in the painting, I again think of Tony. I stand up from my desk, force myself to walk out to the balcony. A bright Florida morning greets me, blue sky, puffy white clouds. The 14th floor condo offers an enchanting view of Sarasota bay—in those places the water is not obstructed by other downtown high rises.

Tony and I bought the place just two years ago. He loved the west coast of Florida so much, was so darling in his childish enthusiasm about moving here. After 38 years working in New York, he had found his tropical paradise. Then he got sick and was gone in less than a year.

Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?

Thankfully, my maudlin reflections are interrupted by the phone buzzing on my desk. I step back inside and stare at the display. Not a number I recognize.

“Yes?”

“Mr. Boucher?” A nervous, high-pitched voice. Her pronunciation of my name makes it sound like my profession is purveyor of meats.

“Boo-chay,” I correct.

“Oh, I’m sorry. My name is Miranda Saty. I understand you are authenticating a painting for my grandmother, Katherine Stuyvesant?”

“Yes. That is correct.”

“I was just wondering if you could tell me—if you’ve come to any conclusions yet?”

Well, young lady. I am not in the habit of disclosing my findings to an unknown voice on the telephone. “Not yet. I will submit my report in writing to Ms. Stuyvesant and her attorney, Mr. Fisch, as has been arranged.”

“Of course … Um, can you tell me when that might be?”

Inquisitive little person. I wonder what this is about. But I see no harm in a straight answer. “I am waiting on the lab results. The evaluation should be complete in three or four days.”

“I see. Uh, Mr. Boucher, I am sorry to trouble you, but I wonder if I might speak with you about this in person?”

Now, this is intriguing. Could she possibly be hoping to influence my conclusion? Stranger things have happened in this business. One way to find out.

“Certainly.”

“Would this afternoon be possible?”

“If you can come here. I’m working today.”

“That would be wonderful. I have my grandmother’s contract here.” She shuffles a paper, reads my address, which I verify.

“Would two o’clock be all right?”

The bell rings promptly at two. When I open the door, my mouth gapes, making me look, I am sure, like a grotesque caricature of an astounded old man.

She looks exactly like the Tahitian girl in the painting.

She smiles and extends her hand. “Mr. Boucher? I’m Miranda Saty.”

I do my best to recover, greet her, usher her into my office. The painting is still on the wall, and I can’t help glancing at it, then back at her. She notices and laughs.

“Forgive me,” I mutter. “There is quite a resemblance.”

She nods. “It’s a bit of a joke in our family.” She sits down in the chair by my desk. “My grandfather always said it was fate.”

Her grandfather, Major Stuyvesant, brought the painting back from Europe after the war. The Major died last year, and now his widow was trying to sort out the estate.

“May I ask, are you part Polynesian?”

“Indian.” An open and unabashed smile. “On my father’s side, obviously.”

“Of course.” I settle into my chair, straining to move past the uncanny resemblance. “What can I do for you, Ms. Saty?”

The amusement leaves her face. “Well, this is a little awkward. My grandmother is in a rather fragile place, ever since my grandfather passed away …”

I recall meeting with Ms. Stuyvesant in her lawyer’s office. A thin old lady, of German or Dutch descent. She was pale, obviously devastated by the death of her husband. Having lost Tony so recently, I could sympathize.

“Anyway,” her granddaughter is saying, “I have no idea what you are going to conclude about the painting. My grandfather always thought it was real, but he never bothered to have it evaluated. I guess you know that already. The thing is, now that he’s gone, my grandmother has gotten it into her head that the painting must be real, and that she’s going to leave it to me. It’s become really important to her, almost like an obsession.” Her voice trembles, her eyes moistening. “I have a feeling that learning the painting isn’t real might really disturb her.”

“Ms. Saty, I can appreciate your feelings, but …”

“Oh no! Please don’t misunderstand. I wouldn’t ask you to say it’s authentic if it’s not. I was just hoping that—if the news is bad, that you might communicate it to me first. I’d like a chance to prepare her, maybe try to keep it from her for awhile, until I can get her focused on other things. She’s very easily distracted these days.”

She gazes at me hopefully. Innocent and full of life, like the girl in the painting. Not so outrageous a request really. Still … “It’s a bit awkward. My contract is with your grandmother.”

“I understand. But you could check with Mr. Fisch about it. I’ve spoken to him, and I think he’ll support the idea—for the sake of my grandmother’s emotional health.” She takes out her phone, starts tapping. “You have my cell number. I’m texting you my email address. If you would please consider it, it would mean a lot to our family …”

“Well. If Mr. Fisch agrees to the idea, for his client’s sake. I suppose I can honor your request.”

That beautiful smile returns. “You’re very kind. I really appreciate it.”

As she’s leaving, she pauses for one more look at the painting. “Real or not, it really is lovely, isn’t it? Do you mind if I ask—totally off the record—which way you are leaning about the authentication?”

I consider again how much she resembles the Tahitian girl, and I smile. “Well, totally off the record—and I am sorry to tell you this, I am 90% sure it’s not an authentic Gauguin. Of course, the lab report might still change my mind.”

She nods, not surprised. Then she surprises me: “Are they using reflectography? Wood light analysis?”

She is shown my renewed caricature of a shocked old man. “I’ve read up on authentication a little,” she says. “I’m a Physics Major at UF.”

“I’m impressed. You’ve done your homework. But actually we’re using a relatively new technique called optical spectroscopy. There’s a state-of-the-art lab at Collins College, right here in Sarasota. So I didn’t need to send the painting out of town.”

“And that test will be definitive?”

“Well, no lab tests are completely definitive, except in the case of poorly executed fakes. For instance, a 20th century chemical showing up in the pigment of a supposed Renaissance portrait. But I’ll be able to compare the findings to a database at the Sorbonne, which has readouts from hundreds of paintings. I expect it will confirm my judgment.”

She nods. “It’s a fascinating field. I do thank you again for your time and your kindness.”

Two days later, the lab at Collins College sends over the results. I spend the morning online, comparing the numbers and graphs to those of several dozen paintings in the Sorbonne database. As I suspected, the profile more closely resembles pictures executed in the 1940s and 50s than ones from the 1890s. The probability of a forgery jumps from 90 to 95%. I’m ready to file my report.

Except, I’m not.

I keep looking up from my computer screen to find the Tahitian girl staring at me reminding me of Miranda Saty, and her grandmother. Sad, fragile old lady, devastated by the loss of her life partner. My report could tip her over the edge into despair.

But what can I do about it?

Tony’s voice jumps into my mind. You know what you can do about it.

“Don’t be absurd, Tony.”

We sometimes have these disembodied conversations, when I’m especially lonely or pressured. My therapist, Dr. Harper, tells me it’s nothing to worry about, a normal symptom of grief. Then he suggests I work on establishing new relationships, maybe try group therapy—Please.

“Really, Tony? I’ve never falsified a report in my life.”

But you’re not totally sure, Henry. 95% is not totally sure. And let’s be honest here, you’re inflating that number. You always erred on the side of caution. Always less risky to claim a picture is a fraud.

That touches a sore spot. Tony used to chide me that I secretly enjoyed declaring frauds. When we first met, I did a little painting of my own—until concluding, woefully but realistically, that I lacked any real talent. Instead, I devoted my life to authenticating works of art, adding in that small way to the sum of beauty in the world.

But what if it was the opposite? What if, by claiming so many frauds, I instead deducted from the totality of beauty?

Might I reverse that course in this one instance?

“No, Tony. My reputation is at stake here.”

“The bubble reputation.”

“Really? Quoting Shakespeare at me now?”

You’re well past the bubble reputation and the cannon’s mouth, Henry. You’re almost to the last scene of all, “second childishness and mere oblivion.” So what does it matter?

I need air. I stand and stretch, walk to the balcony, gaze out over the bay.

Tony was always recklessly compassionate: giving money to homeless people on the street, offering to drive them to shelters. Such a loving heart. He really was the better angel of my nature.

“But consider the ramifications. If the family tries to sell the picture, any buyer or auction house will insist on a second authentication.”

Your judgment will be second-guessed. Not like that hasn’t happened before. Besides, Miranda and her grandmother both said they’re planning to keep it in the family. Most likely it will be years before it goes up for sale. You and Katherine Stuyvesant will both be long gone.

“But to deliberately alter my best judgment …”

You have a chance to comfort an old woman’s heart, maybe save her life. What’s your best judgment about that?

Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?

I stand gripping the balcony rail for a long time. Then, I go back inside and stare at the two women in the painting.

It really is a beautiful picture. Can beauty alone make it authentic?

I sit down at the computer, look again at the Collins College report and the numbers and graphs from the Sorbonne. Am I experiencing a transformation of consciousness? Or simply losing what’s left of my mind?

Almost without realizing it, I start typing the report.

After a few lines, I stop, pick up the phone, and call Miranda.

“Hello, Ms. Saty? This is Henry Boucher. I have the lab tests back, and I’m writing up my report. I wanted to let you know: I have now concluded that your painting is authentic.”

“Authentic” was originally published on the Sarasota Fiction Writers website.

Thanks for reading and please feel free to comment.

Lovely story, Jack. The middle part with the reveal of death after 38-years in New York stood out for me. Maybe because this feels like a familiar story of someone I might’ve known? It almost feels like someone I knew went through the same experience. Though who, I have no idea. The older I get, the less I remember though. So it could be no one at all? Anyhow—hope you’re enjoying the warm weather in Florida, Jack-

Thank you, I really enjoyed this short story.